Our roving cultural reporter Elena Bowes is back in her home town of New York this week, chatting to curator Natalie Bell of the New Museum about Artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and her new show, Under Song For A Cypher.

Our roving cultural reporter Elena Bowes is back in her home town of New York this week, chatting to curator Natalie Bell of the New Museum about Artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and her new show, Under Song For A Cypher.

If you happen to be in Manhattan this summer, make a point of stopping in at the New Museum on the Lower East Side. There on the 4th floor is a quiet, contemplative solo show lyrically titled Under-Song for a Cipher by British-Ghanian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

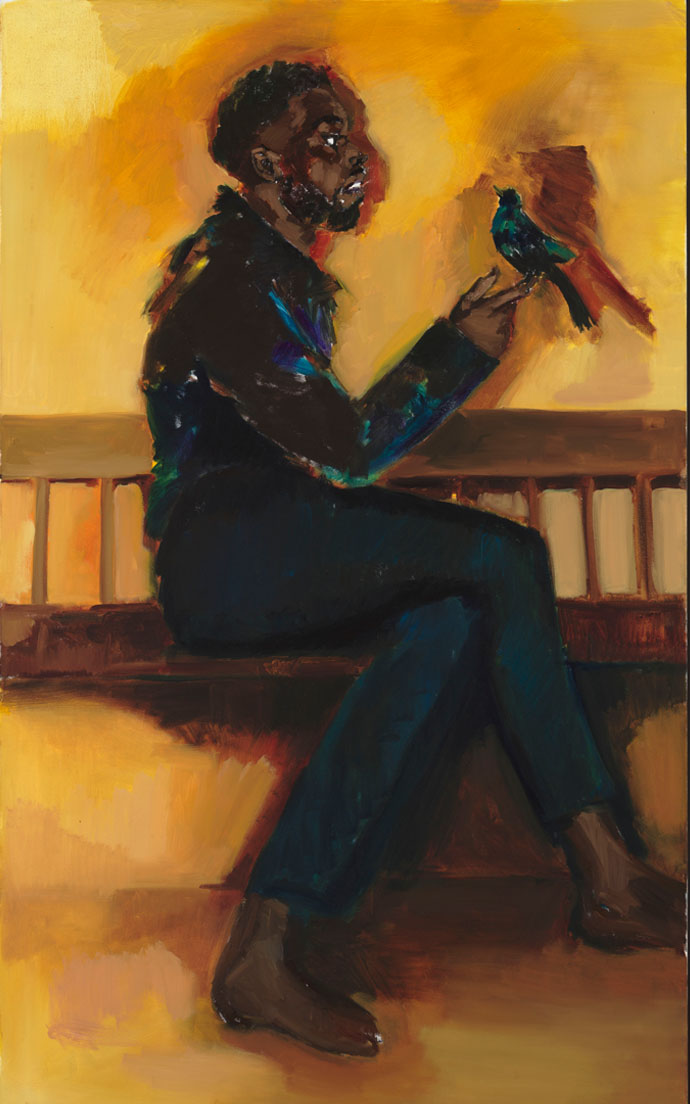

This body of new work, each paired with titles like Vigil for a Horseman or Light of the Lit Wick hang in a single somber room. While Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings appear in several public galleries including the Tate and the Victoria & Albert, the Turner Prize shortlister is not well-known outside the UK. Another reason to make time for this show, which closes September 3rd, is that the talented Yiadom-Boakye is taking a sabbatical until 2019.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Of All The Seasons, 2017

Yiadom-Boakye paints imaginary people born from scrapbooks, magazines, her imagination. Yet they seem so real that they could walk off of the canvas out the door into the Bowery. The figures painted on linen or canvas are all beautiful, all black and all appear to be lost in thought. Alongside each of the paintings are mysterious titles like, Ropes for a Clairvoyant, Mercy Over Matter, In Lieu of Keen Virtue.

“They are character studies of people who don’t exist. Subtleties of human personality it might take thousands of words to establish are here articulated by way of a few confident brushstrokes.” writes British novelist Zadie Smith in an excellent article in last month’s New Yorker.

I discussed this thought-provoking exhibition with curator Natalie Bell.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Mercy Over Matter, 2017

How did the idea of the show come about?

“For these exhibitions that we do in the spring and summer with one artist on each floor, we often try to zero in on an artist who is at a pivotal moment in their careers so thinking about how having a solo museum exhibition can offer an opportunity for them to gain more exposure and momentum at an important time. And we felt like it was a great moment to bring a new spotlight to Lynette’s work in NY. A lot of people in NY still haven’t encountered it.”

Yiadom-Boakye uses subtle layers of muted colours and tones in her paintings, with dabs of vivid reds, pinks, greens and blues. How she applies paint to canvas is just as intriguing as the figures themselves. Most of the 17 portraits at the New Museum are painted on linen, one is on canvas.

She had been painting on canvas and only recently returned to working on linen, according to her London dealer Tommaso Corvi-Mora. This is important because linen takes longer to dry so Yiadom-Boakye who famously likes to paint wet on wet has more time to complete a painting on linen.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Ever The Women Watchful, 2017.

Is it true that when working on canvas, she typically completes the bulk of the picture in a day?

“What she enjoys about the medium (of oil) is the silkiness and the fluidity of working in the oil medium. But once its consistency starts to change, it doesn’t offer the same kind of play.”

What do you like most about her paintings?

“I like how she provides a prompt for the viewer that doesn’t give a whole lot of information. I think that’s where her work has a very conceptual bent to it, in the sense that her project is about activating the viewer’s imagination. And really leaving a lot of work to the viewer in terms of thinking about who these figures might be, what they might be thinking, calling on their own associations, memories things like that.”

“And the other way she does that too is with her titles, she has a command of language that’s lyrical but not too poetic, it’s another way that she offers some suggestions or illusions but doesn’t over-determine her work in any way.”

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 8am Cadiz, 2017

In an interview with you, Yiadom-Boakye said, “I think about the people a lot less than I do the painting” what do you think she meant?

“I think that goes back to the act of painting and the act of mark making. And I think that’s a big part of the reason why she doesn’t depict real people because then you have the problem of fidelity and accurate representation. Does it capture their immaterial characteristics and with an imaginary figure you don’t have to grapple with those questions. You get to really just play with the process and the medium and the technique and that’s what she means.”

“She really loves the problem solving that goes on when you start mixing mediums and putting a mark on a canvas or linen or whatever it is, focusing in, honing in on the human figure. And I think that’s where a lot of her work has its power for people. In that we’re always going to be attracted to the human figure. That’s what humans are coded to do.”

“But her primary project is thinking about colour, thinking about how she can change the tone, how she can resolve some sort of compositional dilemma, and I think the figures are what actually comes from that. The act of painting figures is secondary to the act of painting the painting.”

“She actually just enjoys mixing her paints and painting and problem solving that comes when you’re making a picture, when you’re making something from nothing. You stumble along different challenges along the way.”

She said that she loves Degas, Manet and Sickert. She does paint a lot of dancers.

“It’s a motif that she’s used at various points, and I think she would say that one of the ways that dancers are interesting as figures is the amount of strength that they have. That’s the painters’ fascination with dancers, sculptors’ fascination, that their bodies are trained to make such delicate movements, such incredible strength that that demands. Sometimes it means that a female dancer’s body has almost a masculine muscle. It’s a very toned human body which historically artists have an interest in.”

To me her paintings are a bit melancholic, soulful.

“I find them pensive, there are a lot of figures who they themselves look lost in thought or a daydream or imagining something, and I think sometimes seeing that image is also what perhaps unconsciously prompts viewers into their own imagination.”

“They’re not always smiling or happy or excited or caught in the middle of a thrilling moment. They are usually in a moment where they are reflecting on something or they are pausing. It’s kind of like mental downtime, you have a sense that there’s an imagination or thought happening.”

She paints from her imagination, she paints most of each canvas in a day, any other interesting details about Yiadom-Boakye?

“She teaches in art school (the Ruskin) in the UK, and she’s extraordinarily humble, almost self-deprecating. She’s extremely modest.”

More on the exhibition here. More from Elena Bowes on her excellent blog here.

All images thanks to the New Museum.

Absolutely beautiful paintings. Thanks for posting them!