Anyone who’s walked passed Liberty recently will have seen its excellent tribute to the Suffragette Movement’s Smashing Windows campaign from March 1912, where many of the store’s windows were broken. Nine modern women are celebrated, including Florence Welsh, Anya Hindmarch, Stella Dean, Katherine Hamnet and author Elise Valmorbida, who our regular guest blogger Elena Bowes happens to know. We persuaded Elena to interview her friend, whose book is currently book of the month in The Times, for TWR. You’re welcome.

Who doesn’t love getting lost in a great book? When that book is written by a dear friend, it’s pure joy. Actually, I got so lost in Elise Valmorbida’s The Madonna of the Mountains that while I marveled at her writing initially, soon all I cared about was the story. If you are a fan of Elena Ferrante, Kristin Hannah’s The Nightingale, and Sebastian Faulk’s Birdsong, then you’ll soon get as blissfully lost as I did in this epic novel.

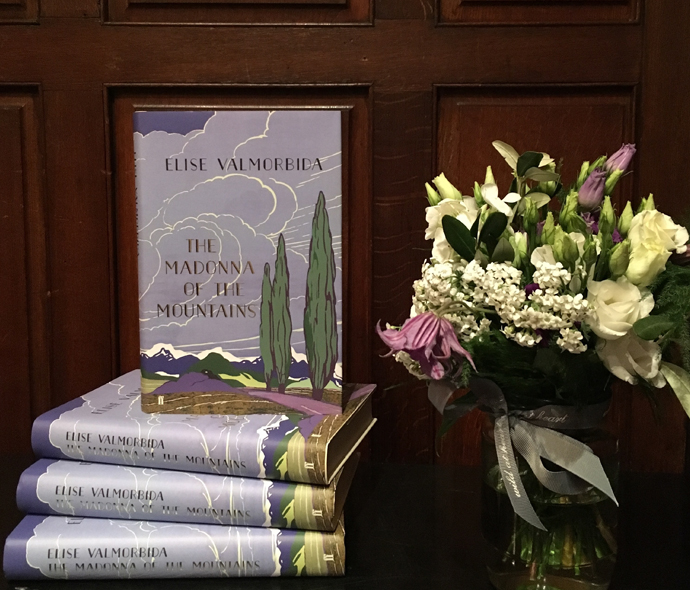

The Madonna of the Mountains is the compelling, detail-rich life story of Maria Vittoria. The novel opens in 1923 when Maria’s father has gone searching neighboring villages to find a husband for his daughter who at 25 is practically a spinster. Valmorbida’s tale spans 27 eventful years, transporting the reader back in time to a distant world where a woman makes do with what she has been given: a quick-to-anger husband, five children and the troubles that come with Mussolini’s fascist reign and world war. She battles fear, hunger, betrayal and guilt as she tries to keep her family together during these war-torn years. This is not a sentimental tale. Valmorbida writes beautifully about real life with metaphors that sing. I’m hoping for a sequel although Elise says while she has a two-book deal with her UK publisher Faber & Faber, nobody is expecting a sequel. Darn.

I first met Elise – who grew up Italian in Australia and then fell in love with London – eleven years ago when I enrolled in her Creative Writing evening classes at Central St Martin’s in London. My marriage was in free fall, and I signed up more as a way to make sense of what was happening to me, than any thought that I might have some talent. From the start, Elise encouraged me to think of myself as a writer and to view my life story as rich in good material. We quickly became friends and met for endless coffees where Elise – always wearing her trademark bright red lipstick – coached and mentored me. She pushed me to apply to be deputy editor of writers’ group 26, encouraged me to get a Masters in Creative Writing at Kingston University and urged me to go on-line and enroll in Match.com – all good material, she said – when I was newly single.

Elise is one of my favorite people – smart, funny, empathetic and strong, not to mention being a truly gifted writer. Below is our interview about The Madonna of the Mountains which is published by Faber in the UK and Random House’s Spiegel & Grau in the U.S.

Elise being interviewed at Liberty earlier this month.

Your novel is brimming with so many vivid details about village life from doing laundry by hand to embroidering wedding linen to cooking snails and lizards when times are tough. What kind of research did you do beforehand? Was there one resource that was especially helpful?

Since moving to London decades ago, I’ve made countless trips to Italy and filled notebooks with random observations on anything from language to landscape. I have vivid memories of sitting at a kitchen table with an elderly relative or neighbour, taking notes and listening to reminiscences and recipes. People liked telling me things, knowing that someone was genuinely interested in this disappearing world and that they would not be forgotten. It was like a long, haphazard, oral history project. Once the novel was underway, my trips became more like focused research missions. I explored historic sites and places that are nowhere on a map. Museums, churches, cemeteries, fields. Local books and films. Local special-interest websites that were impossible to find in the UK. I foraged for facts—and edible wild things. I got lost in eBay, a vast research resource that is full of unpredictable discoveries. Michelangelo Frammartino’s film Le Quattro Volte was a lateral inspiration. It’s set in a place at the other end of Italy, and it’s virtually plotless, but I love its patient, attentive, near-documentary gaze. I wanted that sort of intensity as I described my characters doing the washing or slaughtering a pig.

Your own family migrated to Australia from Italy. How biographical is this novel? Is there a woman in your family who bears some resemblance to the heroine Maria?

Every novel contains elements taken from real life and real people, and there are indeed bits and pieces of family stories in here. My grandmothers, my aunts and great aunts—on both sides of the family—they’d all see details of their lives here. There’s also a huge element of the narrative that emerged from somewhere deep inside of me. I’ve been working on this book for 5 or so years, but in a way it started from a tiny seed a long time ago. I grew up Italian in Australia, and as a child I was spellbound by stories about Italy, world wars, migrations. It would have been sheer wastefulness not to put some of that, and my own personal experiences, into the mix. Even so, if you knew how hard it was for me to create plot, and structure, and ordinary characters in their time—people who are given no voice in conventional historical texts and so are very difficult to research—you’d know how much this is a work of effort and imagination.

In your book, Maria is sometimes referred to as having arms like a man and being the boss of the house. She’s driven, hardworking and resourceful. When she finally gets her visa to emigrate to Australia, the stamp says “Housewife”. How would you describe Maria?

I think of Maria Vittoria as a kind of Mother Courage. She doesn’t have the education or worldliness to analyse ideology, nor the heroism to overcome pragmatism. And she is of her time. She grows wiser with life’s hardships and responsibilities, and she grows older. But she’s no feminist and never will be. After all her work running a business and negotiating the chaos of war, her first-ever passport identifies her as a housewife. It’s in English, so she doesn’t know what the word means yet.

In the novel, the Madonna says “the element of man is the earth. The element of birds is air. That of fish is water, but for women it is honor.” Maria’s daughter Amelia chooses love over honor. Are there messages for the modern woman in your book, both from Maria and Amelia?

I don’t think in terms of messages—if I did, I’d probably end up writing a dissertation rather than a novel! There are significant differences between Amelia and Maria which are generational—mothers, daughters—but such differences are exaggerated by the extreme social change and disruption of war. It seems to me that my characters develop as they encounter challenges. It’s those developments which start to bring themes out into the light—themes such as honour, love, gender, self-determination, forgiveness. I am certainly interested in the muckiness of morality. I like these words by Margaret Atwood in her ‘Road to Ustopia’ essay: “Of course we should try to make things better, insofar as it lies within our power. But we should probably not try to make things perfect, especially not ourselves, for that path leads to mass graves. We’re stuck with us, imperfect as we are; but we should make the most of us.”

Do you remember when and how the germ of an idea for this original novel came about?

Every time I finish a novel, I go into a mild state of mourning. I feel that something significant has gone out of my life, and I miss it constantly. After a while, fear creeps in: what if that was it—the last one? I feel sure I will never write another book. I know the world can live without another book, but can I live without writing another book? It’s almost an essential need. And yet I can’t imagine what I will write about next. With this novel, as with the others, I started in a state of chaotic unknowing. I’d amassed a stash of notebooks full of handwritten scribbles and sketches, random stuff, much of it rubbish. I decided to collate anything and everything to do with Italy, nature, seasons, food, anecdotes, sayings… It was a laborious transcription, but it yielded a single document full of little inspirations. I started writing about a birth in a remote time and place, from the point of view of a newborn baby girl. It’s a chapter that has well and truly vanished. But it got me going, and Maria Vittoria slowly emerged from her.

You write a lot about forgiveness.

When you read conventional historical texts, it’s easy to find out about military campaigns and politicians. Or resistance heroes, leaders, their lovers… But it’s not so easy to find out about ordinary women’s lives. War brings with it many extreme and unpredictable challenges. Who is a hero? Who would risk everything—life, family, survival—to hide a fugitive? Daily life in war is full of mucky moral compromise. Ordinary people do things that they can’t forgive themselves for. But without forgiveness there is no peace.

How has your writing style changed over the years?

It’s difficult to be objective about it. I suppose my writing has changed with me. The biggest change, I think, is that I am now less terrified about plot. I say “less”, because I am still terrified.

You have written a handful of books, both fiction and non-fiction. How was this experience – working with two very polished and successful publishers, Faber & Faber in the UK and Random House’s Spiegel & Grau in the US – different?

My other books were published by small independent publishers. This has been a big adventure—and it continues. First things first, I don’t have just one brilliant editor, I have two! Louisa Joyner, editorial director at Faber & Faber (UK), and Celina Spiegel, editor-founder of Spiegel & Grau, which is an independent imprint within Penguin Random House (USA). What an enlightening experience! Next thing I knew, there were these things called proofs, also known as bound galleys in the States. These are sent out to readers and critics well before the book’s publication, allowing time for juicy quotes—authors Louisa Young and Sara Gruen have both written words of praise for the actual book—and reviews, the first of which has just appeared in The Times, where my novel is “book of the month”!

Was it difficult writing for both an American and British audience?

My day jobs pay the bills, so I don’t write fiction in order to make money. If I were to write ‘for an audience’ I think it would mess with my sense of creative risk. It would be a bit like performing, and safely, self-consciously, rather than writing from the heart. Once my literary agents secured a UK publisher, and then an American one, I started picturing two editions. What would this entail? I’ve heard of novels that have different endings, or chapters removed, or characters who have been adjusted to suit an editor here or there. And titles! Harry Potter’s Philosopher’s Stone became a Sorcerer’s Stone in America. But I was keen to have one book, not two. And it happened. At the US copy-editing stage we ‘translated’ my narrative into American English. That’s more than spelling. It’s vocabulary: railway sleepers became railroad ties, and marrows became squashes, although Autumn did not become Fall. Other bits and pieces, too, but nothing dramatic.

What did you edit out of this book?

My writing process is utterly inefficient. I set out exploring—no, that sounds too pleasantly colourful—I set out groping. And stumbli ng. For a long time. The book’s first draft spanned more decades, more locations, more perspectives, all researched and edited obsessively. After some years, and with constructive advice from my writing group pals, particularly Annemarie Neary, I decided to lop off a third of the text, work intensively into what remained, adding chapters and removing perspectives. It hurt. Not like actual surgery, but no other simile comes to mind. (All the while, I had no idea if one day this labour of love would be consigned to the closet—there’s one broken novel in there already.)You know that Hemingway quote? “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” Melodramatic, but cute.

What advice would you give to an aspiring writer?

Write. Notice. Keep a notebook. Read. Write. It’s a kind of fitness. The more you do it, the better you get at it, as long as you make good use of feedback along the way.

What books and/or authors inspire you?

Shakespeare inspires me above and beyond all other writers. His writing is endlessly intelligent, compassionate, inventive, emotive, profound, silly, poetic, romantic, gross, beautiful, subtle, timeless, cross-cultural, diverse… I love the poetry of TS Eliot and I adore Samuel Beckett’s prose and plays. Virginia Woolf is a deep treasure. Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, Annie Proulx and Michael Ondaatje sing to me. Two slim novels that are standalone perfection: F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and The Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys. Oh goodness, I’ll stop now. Everything inspires me.

What do you do for fun?

How long have you got?

Elise’s novel The Madonna Of The Mountain, is out today, buy here.

If you want to read more about Elise, here is a blog she recently wrote about sewing in the family, specifically her grandmother Clementina who taught Elise how to sew and “properly darn”. Clementina would frequently go to male-run council meetings and speak her mind, always wearing bright red lipstick. Fearless. She reminds me of someone else I know.

Fascinating interview with an amazing woman. Just off to my local Waterstone’s to buy the book…

Thanks for the detailed interview. I don’t know if anyone has noticed that successful women are often more relaxed about marriage. They often have guest marriages or open marriages. This state of affairs does not prevent them from using married women dating – https://www.nastyhookups.com/married/women.html This gives an extra boost to the imagination and has a good impact on their creative life.

This is one of the best sites I have found on the internet until now. Thanks for sharing this post.

In order to create a perfect post on a discussion board – you need to spend a certain amount of time writing it, so that it attracts attention and evokes the emotions that you need. You can contact https://studyfy.com/write-my-discussion-board-post service to order the writing of such a post on the necessary, you, topics

The article ardently recommends “The Madonna of the Mountains” to book enthusiasts seeking an intricately woven tale that intertwines history and human emotion. For those intrigued by this insightful critique, considering a purchase article review could deepen the appreciation and understanding of Valmorbida’s work, unraveling its nuances and the layers of depth in both storytelling and historical significance.

Elena Bowes’ conversation with Elise Valmorbida not only highlights Liberty’s nod to the Suffragette Movement but also underscores the power of narrative in literature and history. Similarly, in academia, weaving a compelling story around statistical data is crucial in dissertation writing. The website URL specializes in dissertation statistics help, aiding students to blend rigorous statistical analysis with clear storytelling. For those looking to enhance their dissertation with precise statistics and narrative depth, consider the dissertation statistics help for a blend of analytical rigor and storytelling clarity.